We know your name, and we know that you are now WACSOF’s general secretary. Now, please Tell us a

little more about yourself other than your name and current position so we can know who you are

in relation to the position and why you have been chosen to be the WACSOF General Secretary at

this point.

I will just be very brief and relate your question to the position as requested. After all, I am having this interview mainly because I am the current General Secretary of WACSOF. First of all, let me say I am a citizen of Nigeria but a son of the West African region. I love West Africa—its glorious history, its people, and their arts. I have lived all my life in Nigeria, West Africa, and only travelled to stay for short periods in other places. The longest period I have stayed out of West Africa has been 3 years.

Kenya, where I was heading an organization that was very similar to WACSOF. So, I can say that I know West Africa quite well because, through my work, I have had the opportunity to travel across West Africa and encounter it on a large scale. I also have an educational background in International relations and have received extensive training on subjects relevant to development and regional integration challenges that West Africa currently faces, especially those of Governance, Democratization, Public Policy effectiveness, Humanitarian emergencies, peace and security, etc. I speak French and English, so I can engage very comfortably across the WA region. So I have a fair understanding about the development issues of West Africa, as well as the multi-level governance architecture currently in place in West Africa, the apex of which is ECOWAS. I have spent most of my work life within civil society, with more than half of that period being spent in the management of civil society collaboration and advocacy platforms at different levels in Africa. It would interest you to know that I worked with WACSOF in the past as a Programme officer. After which, I moved on to consecutively head two other civil society collaboration institutions in Africa—that is, the CAADP Non-State Actors Coalition (CNC) at the AU level and the West African Democracy Solidarity Network (WADEMOS) at the ECOWAS level. So, I can boldly say that I do understand civil society coordination very deeply, and that is what my current position requires. So, I am confident that being the General Secretary of WACSOF at this very crucial moment is an opportunity to deploy all my years of experience in civil society coordination to turn it around.

You were once a programme officer at WACSOF and also a consultant to WACSOF, and eventually you are just resuming your role as its general secretary. Looking back over the years and seeing all the ups and downs that the organization has gone through, what do you think is the problem with WACSOF?

Well, it is indeed sad to say it, but the truth must be acknowledged: WACSOF has indeed gone through serious, even life-threatening, ups and downs several times in its lifetime. Even at the moment, WACSOF is trying to get out of another bout of such challenges. It would appear therefore

that the organization’s case is hopeless to some. But you know, the beauty of it is that when it goes down, it has always come up, just like you said—ups and downs. This is exactly the fourth time such an event has occurred for WACSOF, and in strikingly similar ways. So it appears that there may be a fundamental problem with the institution that needs to be fixed in order for the organization to move forward. I intend to study critically, put my finger on that specific issue about the institution that needs to be addressed, and then solve it once and for all.

So, focusing on the actual problems of WACSOF, I would be bold to say that the key problem of WACSOF is foundational to all the others that might have come about. In other words, it is one problem that is responsible for all the others that anyone may diagnose. And all the time that any of its offspring problems come up, the same solutions and approaches have always been applied with temporary results, but soon again the same problem comes up. This is the problem we are talking about. has manifested time and time again in the same form, that is, in the form of a struggle between the WACSOF Executive Committee and the WACSOF General Secretary about who is legitimately in control of the organization or not. Of course, there are usually other nuances and triggers for the problem, but that is the truth. But this constant struggle between executive committees and general secretaries is only a symptom of the main problem. From my perspective, the main problem of WACSOF is one of institutional design and development.

I, alone, may not be able to articulate it fully and clearly. But in my opinion, when WACSOF was formed in 2003, not much thinking was done in relation to establishing a plan to guide its institutional development and organisational evolution trajectory. Not much work was done to

properly elaborate WACSOF’s unique niche, programming strategy, its stakeholders, and how they can all be carried along in its institutional set-up. As a result, how WACSOF was at the beginning of 2003 is still how it is now—nothing much, if anything has changed. WACSOF is known for some of its institutional structures, systems, and processes, but also for the fact that they are all not functioning well. They are more or less operated through poorly defined informal rules rather than codified institutional management best practices and professional standards. There is often heavy politicization and individualization of its activities, especially along the language divide. Aside from

occasional meetings and the production of corresponding reports, WACSOF has achieved very

limited progress in informing, orienting, organising, and aggregating civil society aspirations for constructive engagement with its primary partner, the ECOWAS. In short, at every stage of its existence, WACSOF has always been challenged as regards its ability to achieve its mandate.

WACSOF is therefore yet to meet the expectations of emerging as a veritable, trusted, and reliable partner.

Some assessment efforts have in fact touched on the issues that I have raised above in different ways within their findings. These include a Needs Assessment of the West African Civil Society Forum done

by WACSI in 2007 as well as references made to WACSOF in the outcome reports of the Regional CSO Meeting on Non-State Actors (NSA) Engagement with ECOWAS, commissioned in 2021. So I am not talking out of the blues. These are real problems that WACSOF needs to solve before it can move

forward towards achieving its mandate. In fact, as a result of frustration with this perennial problem of WACSOF, several civil society organizations across the region are getting together to see ways of evolving a platform that replaces WACSOF.

As a follow-up question, having defined and described what, in your opinion, is the problem of WACSOF, can you tell us what you are planning to do to address it?

I am someone who always looks at any challenge from the bright side and tries to dwell more on the positives of any situation. So for me, looking at the problems of WACSOF over the years, I see only an organization with a high level of resilience in the face of constant challenges, and I am optimistic that this resilience is what will keep WACSOF going, and as well, it is that resilience that will lead WACSOF to the solution it currently needs. Let me digress here to give a vivid picture of what WACSOF truly represents. I must say that WACSOF is a very unique organization like no other globally in its own right. There is no other organization like WACSOF all over the world that preceded it in existence—it is an archetype of its kind all over the world. In fact, most organizations like WACSOF across the world came up one way or another in reaction to what was done at WACSOF.

Whether it is EACSOF, SADC-CNGO, AFDB CSO Platform, etc. all of them were formed in reaction to how novel the concept of WACSOF was at that time. That is why a solution must be found for the

perpetual institutional problems that keep coming up within WACSOF.

As I have already mentioned when I was answering the previous question, the problems of WACSOF have been outlined in some reports, so the work to be done is already under way. Now what remains is to use the findings of those reports to define solutions for the problems. So my intention is to synthesize the outcomes of those reports and use them as a basis for extensive consultations with civil society across the region in order to establish a set of solutions based on the suggestions coming from civil society themselves. As one of the reports puts it, we shall call these sets of solutions “THE WACSOF WE [CIVIL SOCIETY] WANT”, which shall be an effort led by major civil society networks and organizations in West Africa along with the WACSOF Regional Secretariat. The outcomes of these

consultations shall produce a report which will be implemented, in order to evolve WACSOF anew with a strong institutional core that will allow the organization to function effectively.

I intend to use the outcome of that consultative process to define a path forward for WACSOF. The consultative process should be able to address the issues globally, from the root causes to the manifesting problems. Hence, the outcome of that consultative process will include a comprehensive review of the institutional set-up of WACSOF, including a clarification of the roles of the different institutions and aspects of their functionality. The outcomes of such a process will be used to develop an institutional development strategy and trajectory over several years. It shall be used to put in place a process that will transform the organization for impact by

standardizing operational procedures and modernizing its activities through adopting international best practices as we move. We shall institute processes, systems and strong institutional

arrangements that will serve the purpose of effectively organizing civil society better across West

Africa. Beyond that, we shall bring in strategies, programmes, and activities that will add value to civil society and enhance civil society activity as a compliment to the efforts of West African governments as well as ECOWAS.

There are some discussions going on around how civil society can best contribute to ECOWAS, aside from through WACOSF. So, beyond WACSOF, how do you think civil society can be better positioned to contribute to the ECOWAS agenda?

For civil society, the constant search for avenues and opportunities to engage government and other actors is a permanent feature. Civil society needs more opportunities to contribute to the ECOWAS agenda. As a matter of fact, ECOWAS should ensure civil society participates in its planning and programme implementation processes; the same is true for the ECOWAS countries. ECOWAS should create more opportunities to interact with civil society so as to harvest as much as possible from their own raw, real-time knowledge base. Let me also use this opportunity to talk about something that is currently going on: the conversation around the formulation of an ECOWAS-ECOSOC—there is currently an on-going conversation about the formulation of an ECOWAS-Economic and Social

Council (ECOSOC). A popular thread in this conversation is that ECOSOC is coming up to replace WACSOF in the ECOWAS-CSO interface structure. I think this is a myopic view of the role of ECOSOC, and I must say that the conversation should not be about that. I would rather see these ECOSOC formulation issues differently as something that only compliments WACSOF. In fact, I do welcome this idea or conversation with open hands because such a structure, when it comes, will definitely provide

another entry-point opportunity for civil society. Yes, indeed, WACSOF has suffered so much weakness, incapacity, and uncertainty over the years, as I have mentioned earlier. But despite that, it

is still an entry point into ECOWAS for civil society, no matter what. It would be good to have another alternative entry point. So civil society will now have two entry points into ECOWAS: WACSOF and ECOSOC, and then they can contribute more to the ECOWAS agenda. That to

is a huge opportunity that all civil society should get behind. But the difference here is that these

two entry points are of different kinds: while one (WACSOF) is somehow outside of ECOWAS and is an autonomous and civil society-self-regulated space, the other (ECOSOC) would be a regulated

space for civil society constructed by ECOWAS. One provides a space for civil society to self-organize

and engage from their own perspectives; another provides a regulated space for civil society to interact with ECOWAS in a way that touches strictly on ECOWAS’ objectives and programmes. It is like two parts of one coin: while WACSOF tells ECOWAS what it thinks ECOWAS should hear, ECOSOC will respond to issues in the way ECOWAS wants it to respond.

So in specific terms, kindly outline some of your priorities as you step into the office of WACSOF general secretary?

My priorities are as follows:

- Stabilize the WACSOF institution and bring it clearly out of the current challenges it is facing. In that regard, I shall work out with the WACSOF team to regain the confidence and trust of civil society and partners by ensuring that the institutional arrangements are functional once again. By this, I mean the National Platforms and Thematic Mechanisms, the Secretariat, the Executive Committee, and the People’s Forum are all functioning properly. A lot of civil society organizations are losing hope in WACSOF. So in order to get its legitimacy and reputation back, its stakeholders must see that it is now a functional institution and that what the organization is doing captures their own interests, or there is an entry-point for their own interests to be represented in the institutional set-up. I hope to provide strong and focused institutional leadership to the organization and to civil society across the West African region.

- The second priority is to win back the trust and attention of the partners who have become discouraged because of sustained infighting. Chief among these is to secure the trust once more of

ECOWAS. Other valued partners, including GPAC, Ford Foundation, WACSI, OSIWA, etc. will be pursued. But these all will not look the way of WACSOF unless they are sure that such WACSOF debacles, as in the past, do not occur again in the future. They will definitely want to be sure that the support they give does not go down the drain, is diverted, or does not create the desired impact. So I want to build a strong institution with standard operating processes, systems, and units that will ensure the organization stands firm to achieve its goals. This will mean building a professional and goal-oriented organization with staff and leaders that are capable of generating and driving innovation. - I intend to lay a plan to progressively develop WACSOF into a viable and credible institution with functional processes to aggregate and promote civil society perspectives and inputs to the work of ECOWAS, its primary partner.

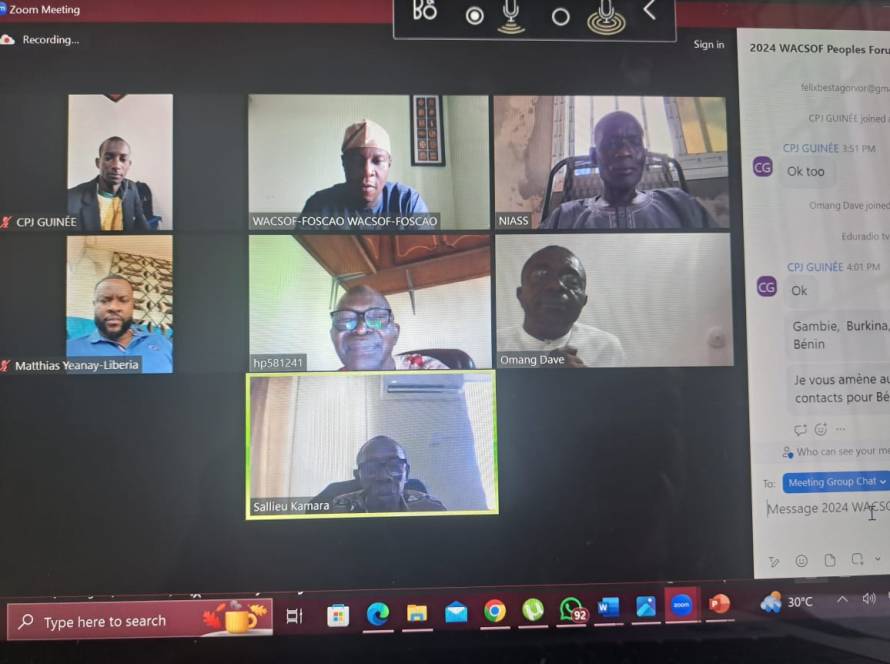

- The starting point of all this is for the organization to rehash its vision, strategy, and leadership, and this can happen only with an extensive civil society consultative process that will lead up to the convening of a WACSOF Peoples Forum where civil society will meet and put heads and thoughts together in order to forge their ideas and visions for the organization. We shall organize a resounding WACSOF Peoples Forum that will refresh the institution with new leaders and new priorities that reflect contemporary developments and realities in the region.

Now let us turn to civil society in West Africa as a whole. What, in your view, are the challenges currently faced by civil society in West Africa?

I will respond to your question vis-à-vis my current responsibility at WACSOF at the moment because that is going to be my greatest preoccupation in the coming days, weeks, and months. The following

Here are some of the challenges that I see: Diversity and plurality: civil society in West Africa is very diverse and pluralist. There are differences.

mandates and different interests—for every issue to be addressed, you will find several similar Civil organizations or networks trying to address it, in different ways/ with different methodologies; different kinds of civil society organizations – networks, alliances, coordination platforms working on different things and organized in different ways. How to get them all to work together with minimal friction is a difficulty, how do you build a structure that is bigger than all these, and that will contain them. It is like when you have a very rich harvest and you have nowhere

to gather all your harvested crops. If now these crops you are talking about are human beings, then each of them would like to find a secured place to be, where it will not be exposed to the harsh

weather condition. Such a situation tends to bring about unregulated competition among civil society – competition for space, funding, recognition, etc. civil society in West Africa is very divers

and pluralist. While this is not a problem of itself, the civil society experience it as a problem because the space has not been organized well enough for them to thrive. Weakness of coordination and collaboration arrangements among civil society – I already alluded to

this when I talked about the challenges of WACSOF but let me try to re-animate it here in summary.

WACSOF as the civil society coordination and collaboration enhancement platform has not fulfilled its mandate effectively. Hence, anything goes for civil society, to the point that some civil society

networks in West Africa can even compare themselves to WACSOF, or place themselves on the same or even a higher pedestal than WACSOF, because WACSOF has not done what it is meant to do.

What there is in West Africa is a huge confusion called civil society organizations involved in a free for-all fights for space, anywhere they can get it. Such a situation fosters a lack of understanding and knowledge about the role of civil society and the opportunities available for civil society to contribute to change in West Africa.

As trivial as it seems, language is also a key barrier to civil society collaboration because it can prevent or inhibit communication among civil society. We see the issue of language coming up strongly from time to time in different efforts at collaboration by civil society in the region. For

example, most efforts at collaboration in West Africa eventually descend into segmentation in terms of language groupings, and these eventually solidify to become silos that serve as barriers to the

same collaboration that was started. To think that Language barriers become a problem for collaboration among civil society in Africa is absurd, because these are colonial languages.

Normally, people would mention the likeliest of all the culprits, funding, as the first point when asked this question. So even though I will mention funding, I will not mention it in the same light as others, because I do not see funding as a challenge. Funding is always available where there is

something genuine and important to be done. The problem is that many organizations hardly have a track-record to demonstrate their capacity and they hardly follow the prevailing trends related to

their work, so when they seek funding they are not seeking it to address current realities but obsolescent issues. It is just like business – if one has a really innovative or revolutionary idea or product to sell, they will always get an investor or a buyer for they work hard at it. Perhaps, the idea

is to work towards ensuring that capacity building and information dissemination programmes are rolled out for the generality of the civil society in West Africa to enable West African civil society to

be on the top of their game with regards to the ideas around which they define their programs. That is a major area in which the mandate of WACSOF may be useful to civil society.